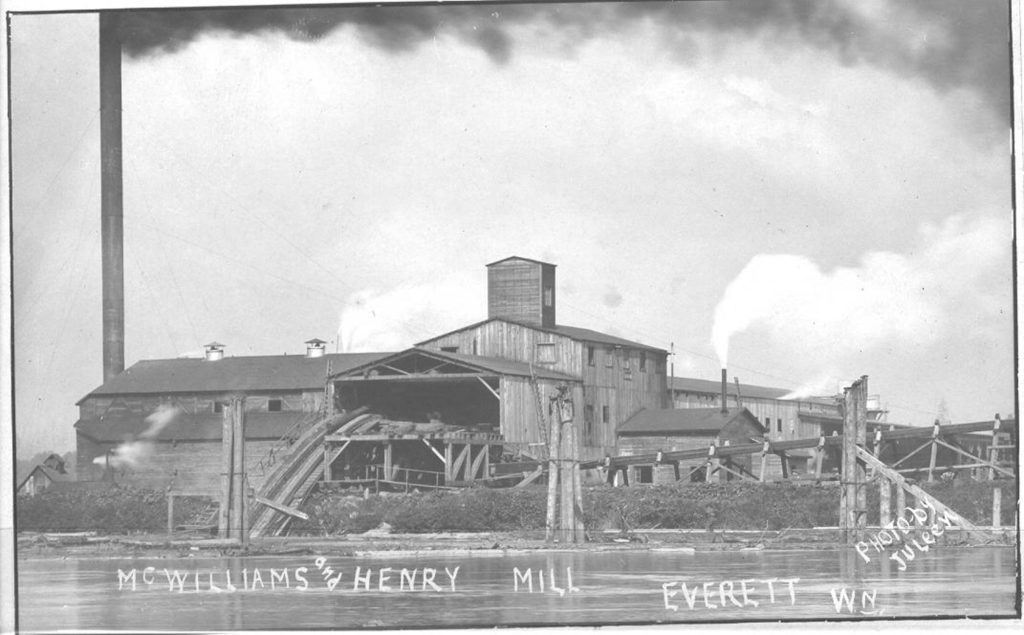

Once proudly called the “City of Smokestacks,” 19th- and early 20th-century Everett was a blue-collar, union, mill town with two dozen saw mills and shingle mills.

But most worker faced long hours and extremely dangerous working conditions.

Accidents are so common that frequently a shingle worker is recognized by his missing fingers, lost in accidents with unguarded saws, and 15% of all deaths recorded in the city in 1909 are from mill accidents.

By the early 1900s, in reaction to this environment, much of the city’s male workforce is unionized. With twenty-five different unions, local Labor support is so strong that in January 1909 the region’s Labor Journal begins publication from the local union hall on Lombard Street gaining Everett regional prominence.

Recovering from a sharp recession in 1914 that allows mill owners to lower pay rates, Everett mill workers are still not receiving their previous scale pay by 1916. In the spring of that year, 400 shingle workers vote to strike in hopes of regaining their pre-recession wage scale. As part of a growing regional center, with a population around 35,000, local mill workers are proud of their status as trade workers and members of the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Yet, they often find themselves at odds with the more radical Industrial Workers of the World (Wobblies) who want to create a union that includes unskilled workers.

On August 19, 1916, Strike-breakers, hired by mill owner Neil Jamison, attack picketing AFL strikers while the local police look on maintaining that the waterfront area being federal property is beyond their jurisdiction. When strikers retaliate later that evening, the police intervene proclaiming the strikers have crossed the line of jurisdiction. On August 22, when twenty-two AFL members speak out about the incident they are quickly arrested.

Throughout September and October of 1916 groups of Wobblies, using their right of free speech on the streets of Everett, specifically a soap-box oratory on the corner of Wetmore and Hewitt, are arrested and beaten by local law enforcement. To challenge the local law, especially Snohomish County Sheriff Donald McRae, a former shingle worker, the Wobblies encourage an environment of free speech, and local readily join in. One local woman is even pulled off of the soap-box for reciting the Declaration of Independence.

In reaction to the spectacle that the soap-box oratory has become, in mid-October, forty Wobblies are escorted by deputies to an area known as Beverly Park where they are brutally beaten and told to get out-of-town. Despite severe injuries, some are forced to walk the 25-mile Interurban Trail back to Seattle.

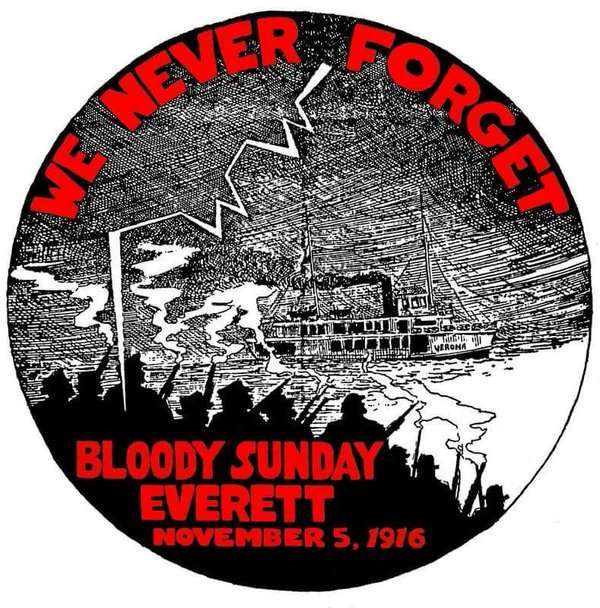

After 150 deputies force Wobbly soap-box speakers to run a gauntlet where some are impaled on spiked cattle guards, the Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W.) call for a mass meeting in Everett on November 5.

The Wobblies vow to return, in greater numbers, to show solidarity for their cause.

Affairs between the Unions and law enforcement are swiftly coming to a head. And on Sunday, November 5, 1916, the bloodiest battle in Pacific Northwest labor history occurs.

On that day almost 300 members of the I.W.W. board the steamers Verona and Calista from Seattle and head north to Everett. The I.W.W. plan a public demonstration for that afternoon on the corner of Hewitt and Wetmore, the same spot used by local Wobblies.

They hope to gain converts to their dream of a single world-wide union.

On November 5, word reaches Everett law enforcement that a group of armed anarchists are coming to burn their town. Under the authority of Sheriff McRae, 200 citizen deputies meet on the docks at the base of Hewitt to repel the intruders.

The Verona arrives first, pulling in alongside the dock.

Sheriff McRae asks, “Who is your leader?”

Informed “We are all leaders!” he announces to the passengers that they are not to land. A single shot is fired, followed by minutes of chaotic shooting. To this day no one knowns if the first shot came from the boat or the dock.

Attempting to avoid bullets, Wobblies aboard the Verona rush to the opposite side fo the ship, nearly capsizing the vessel. Captain Chance Wiman ducks behind the ship’s safe, a fortuitous move when over 175 bullets pierce the pilot house. Warning the Calista not to land, Captain Wiman struggles to back the ship out of port and return to Seattle.

On the dock, Deputies Jefferson Beard and Charles Curtis lay dying, and 20 others, including the Sheriff, are wounded. On the Verona’s deck, Wobblies Hugo Gerlot, Abraham Rabinowitz, Gus Johnson, and John Looney are dead and Felix Baran is dying.

While the official I.W.W. report lists five dead and twenty-seven wounded, it is more likely that as many as twelve Wobblies lost their lives, their bodies disappearing into the bay after the Verona’s far railing broke.

The Federal Government deploys National Guard troops to Everett and Seattle to keep the peace and citizens remain fearful for days. Seventy-four Wobbly passengers are arrested upon their return to Seattle and eventually taken to the Snohomish County jail.

All but one are released.

Teamster Thomas Tracy is charged with murdering Deputies Curtis and Beard, but in a dramatic and much publicized trial that follows, Tracy is acquitted.

The Everett Massacre appears in newspapers throughout the United States. Today, it is still considered one of the most significant events in 1916 America.